Pranay Somayajula, on screen, remotely addresses attendees during the “Holi against Hindutva” teach-in event at Oberlin College, Sunday, April 21, 2024, in Oberlin, Ohio. (Photo by Sayanth Shajith)

(RNS) — On Sunday (April 21), a group of about 40 students gathered at Oberlin College, near Cleveland, for a student-led event called “Holi against Hindutva:” a teach-in aimed at discussing Hindu nationalism’s “violent implications for Muslims worldwide and connections to Zionism.”

An initiative of this sort is not uncommon on college campuses, especially those, like Oberlin, with a historical orientation toward social justice. But this event, organized by Oberlin’s Asian American Alliance and Muslim Students Association, spurred controversy far beyond campus.

The day of the event, demonstrators appeared at Oberlin to protest, holding signs reading “Protect Indigenous Traditions,” “Preserve Holi, Reject Hinduphobia” and “Stop Spreading Hatred Against the Hindu Community!”

The protesters, according to Rakesh Ranjan, president of the Cleveland chapter of Coalition of Hindus of North America, which led the protest, were objecting to the use of Holi, a holiday that celebrates spring and promotes forgiveness and love in the manner of the deities Radha and Krishna.

“They are misusing and appropriating our sacred Holi festival for political reasons,” said Ranjan.

Numerous Indian news outlets picked up the story, and thought pieces from Hindu YouTubers and X’ers went viral.

Demonstrators with the Cleveland chapter of the Coalition of Hindus of North America protest a “Holi against Hindutva” teach-in at Oberlin College, April 21, 2024, in Oberlin, Ohio. (Photo courtesy of COHNA Cleveland Chapter)

In 2020, a nationwide movement called Holi against Hindutva — a word meaning “Hinduness” that has come to represent Hindu supremacy or nationalism — hit Columbia and Harvard and 19 other campuses. Many Hinduism advocates were similarly angry, charging that an anti-nationalism campaign centered on a Hindu festival was “anti-Hindu.”

In Ohio this week, Ranjan further complained that Oberlin’s discussion included no “pro-Hindu speakers.” “If you want to have a fair dialogue with good intentions, you’ve got to have all the stakeholders there.”

Pranay Somayajula, director of research and advocacy for Hindus for Human Rights and a keynote speaker at the event, said he has come to expect backlash when speaking out against Hindu nationalism but was surprised at the scope of the protests — notably, he said, from nonstudents “who had nothing to do with Oberlin College.”

Somayajula said “members of the Hindutva ecosystem” have tried to intimidate and harass students and professors who speak out against Hindu nationalism. “They’re absolutely contributing to this climate of suppression of free speech on campuses,” he said.

Somayajula pointed to a barrage of critiques against Oberlin student activists on social media. Many of the posts, he said, had an anti-Muslim bent. Commenters directed their angry words to the Muslim Students Association, asking if it would be acceptable to have an “Eid against Extremism” event.

In response, the Muslim Students Association and the Asian American Alliance said: “Attempting to discredit legitimate critiques of a right-wing nationalist movement by pointing fingers at Islamic extremism is a blatant whataboutism that does not contribute to the conversation we want to have. The harmful rhetoric propagated and weaponized through online platforms only solidifies our stance against hatemongers.”

Oberlin’s MSA told Religion News Service it would “prefer not to comment” on the situation. Oberlin’s head of communications said the college has nothing else to add at this time.

Though the event’s protesters were not affiliated with Oberlin, they credit a group of college students for alerting them of this event. Hindu on Campus, an anonymous watchdog initiative started in 2021 that now has more than 40k followers on X, said it was notified of the teach-in by a concerned Hindu student at Oberlin, who sent in the complaint but then swiftly deactivated their social media account in fear of backlash.

“It’s a beautiful thing that even if there’s just one Hindu somewhere in rural Ohio who has a problem, the next day, the whole world knows about it,” said a member of Hindu on Campus who preferred to remain anonymous.

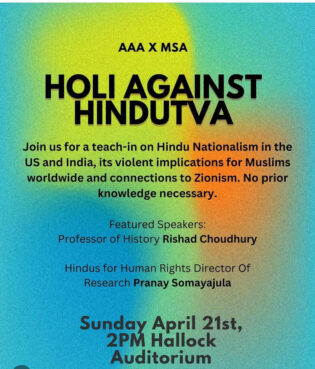

Flyer for the “Holi against Hindutva” teach-in at Oberlin College. (Courtesy image)

But she said some Hindu students are on small campuses with no Hindu organization, and they don’t always have the space to express their views about Hindutva, which she says is highly misconstrued both by faculty and other students.

The group’s demands were simple, said the Hindu on Campus member: Change the name of the event, and allow for Hindu voices to speak on the “dominant Hindu perspective.” There was also the suggestion by others that non-Hindu students should not have participated in an event based on a Hindu holiday.

The HOC member said she was satisfied that the Muslim Students Association took the event off of its social media page, which proved that “there are some boundaries you cannot cross,” such as attacking a community’s holiday.

Nimala Sivakumar, a freshman at Oberlin and member of AAA and the South Asian Students Association, said she had identified herself as Hindu in defending the event online. But after she did, internet trolls found her personal Instagram account and posted comments that derided her physical appearance or that said she “doesn’t deserve to wear a bindi” because she’s not a real Hindu.

“It’s so hard to have conversations with people who immediately lash back at you if you bring up a point,” said Sivakumar. “They say that only Muslims organized the event, and when we say Hindus were involved, then those Hindus are ‘race traitors.’”

Part of the rancor that came out of the Oberlin event, people on both sides agree, is the small number of Hindus at some smaller schools, meaning that student organizations, such as Hindu YUVA and Hindu Students Council, are not large enough to represent the breadth of Hindu perspectives or don’t exist at all. SAHI, the group that began Holi against Hindutva, has vanished since 2021.

As a result, Hindu students join Asian, Indian or South Asian student associations, which may not always touch on the unique concerns of Hindus, but according to Sivakumar, do provide cross-regional events, such as a Kashmiri cultural celebration, that wouldn’t necessarily be possible in a solely Hindu space.

“Hindu student groups might be really difficult to come by, because there are so many people and so many different opinions,” said Sivakumar, who feels “lucky” to have a space to meet South Asian students across cultural and religious identities at a predominantly white institution. “They would inevitably have to address both Hindutva and violence against Hindus in Pakistan, and a bevy of other things.”

Rishad Choudhury, an academic and South Asia historian at Oberlin who spoke at the event, said he was invited by students to supply historical context to a student-led discussion, which he did “without either endorsing or opposing the political aims of the event, which were programmatically pitched against Hindu nationalism.”

But Choudhury said it was regrettable that students in the AAA and MSA were “inappropriately and incessantly trolled in the lead-up to the event,” actions he says were motivated by “knee-jerk reactionary politics that bristles at any criticism of Hindutva.”

“Campuses have of course now become lightning rods for debates over free speech, its licenses and its limits,” he said. “That even a bucolic Midwestern campus like ours should have attracted outside protesters tells you something about how this has become a national issue.

“I very firmly believe they have every right to determine for themselves their own political orientations,” he added.

Discover more from CaveNews Times

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

![Exploring the Serene Beauty of Nature: A Reflection on [YouTube video title]](https://cavemangardens.art/storage/2024/04/114803-exploring-the-serene-beauty-of-nature-a-reflection-on-youtube-video-title-360x180.jpg)