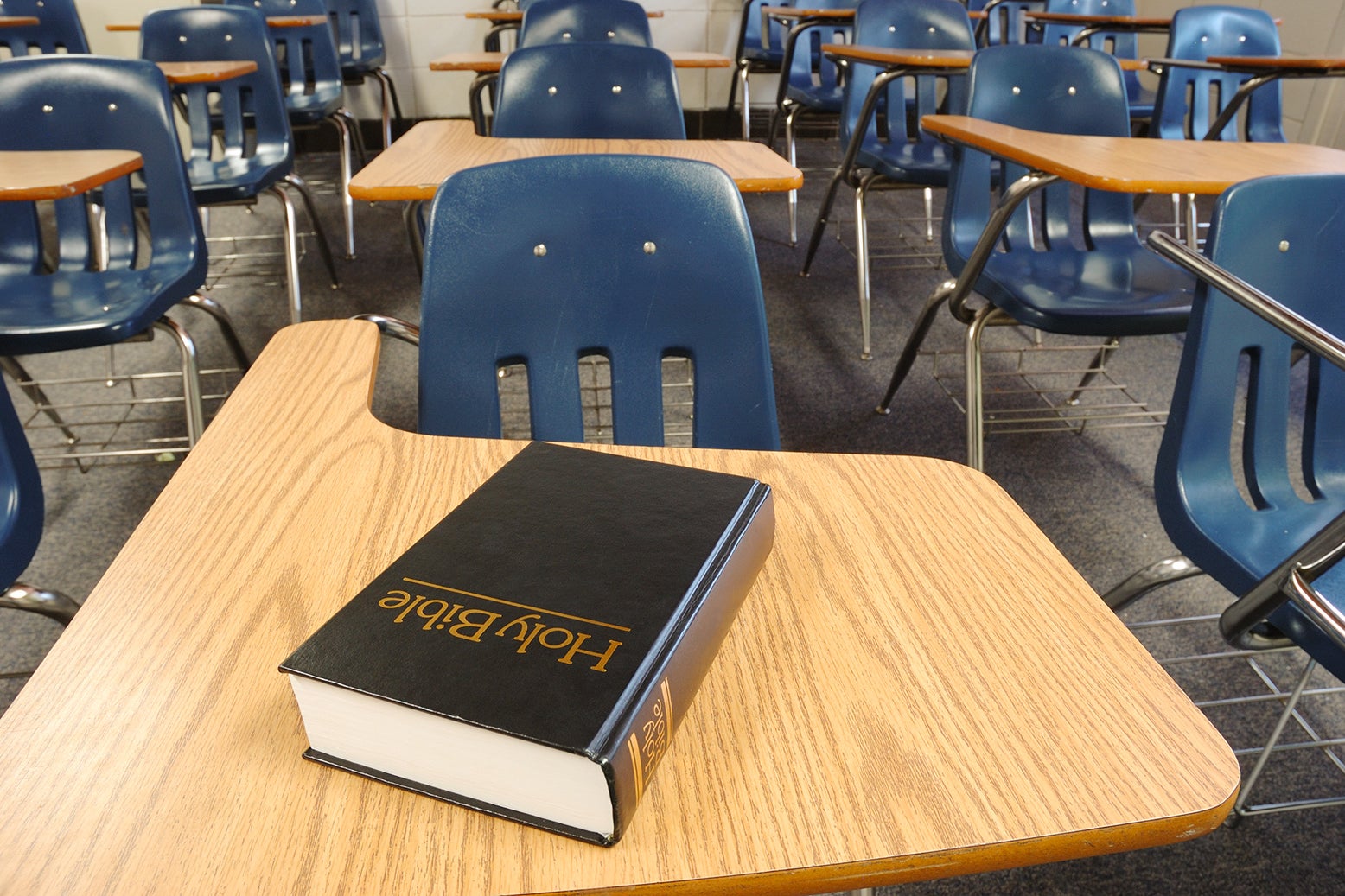

I love teaching the Bible to mixed groups of students. But it’s hard!

As an English professor with a divinity school degree and a deep love for the Bible, I have for 20 years taught a college class that’s now called Reading the Bible. So when I read news stories like the one from Texas before Thanksgiving, in which the state Board of Education has voted to allow K–5 schools to adopt a state-authored curriculum built around the Bible (and has financially incentivized that curriculum’s adoption), I’m always curious.

Curious is the word. It’s not outraged or indignant. I think it would be nice, after all, for everyone to learn a lot more about armloads of ancient texts and traditions: Genesis, yes, but also Babylonian and Cherokee creation narratives, stories and hymns from the Vedas, long sections from the Analects, Mencius, and Zhuangzi. Collectively, we share so many stories and heritages that I’m disappointed when curricula approved by boards of education ignore nearly all of them.

Mostly, however, I’m curious how these boards imagine pulling off what seems to me to be a towering feat. It’s a quartet of feats, really: to ask 1) public-school teachers to teach 2) the Bible to 3) young children without 4) the defining context in which the Bible has nearly always been read—that is, within communities committed not to excerpts but to the whole.

The class I teach used to be called, as such classes were, The Bible as Literature. But for the sake of truth in advertising, and because there never was a bright line between reading as literature and reading as, say, history or politics or religious studies, I changed the name to reflect what we do. We read. And reading is hard, let alone Reading the Bible, in translation, in a college classroom. And I’m trained to do it. And these are college students.

I teach at a secular institution, an engineering school, so there’s no attempt to convert people. I’ve had students drop the class because it’s not Sunday school. One stormed into my office to thunder at what he called my insufficient fear of the Lord. Another dropped the class because, he said, he was an atheist and had hoped for mockery of the Bible. Most students stay. They’re a mix. Some want to learn as part of their practice, as devotion. Some are holding to the light their hand-me-down faith traditions, testing the seams and looking for holes. Others are neither Jewish nor Christian nor Muslim, just curious. Some say they’re “nothing.”

It’s always hard. A slip of the tongue, even from a well-intentioned teacher with years of scholarly training and years of practice, and I might slide from speaking as a professor to speaking as a devotee. In the classroom, it’s my job to ask, “What does the passage say?,” not “What does God say?”

Any curriculum, any teacher, might easily misrepresent the Bible. Texas’ Bluebonnet Learning curriculum, for example, says that in the beginning, according to Genesis, “there was only darkness.” That’s not at all what Genesis 1:2 says. It describes earth and waters, some kind of mythical abyss, not to mention “the breath of God hovering.” Both the seven-day story of creation in Genesis 1 and the Garden of Eden story that follows are stories. They’re narratives. Neither one is an “account,” really, let alone a “history.” Maybe the word mythos, with which Karen Armstrong characterizes these texts, is fair enough.

But it’s only fair enough as long as it’s clear what exactly she means by the term. What tests or training will ensure that a public-school teacher can speak so precisely and knowledgeably? Will teachers know not to ask, when trying to prompt discussion, “What is God saying in this passage?” What guarantees that each kindergarten teacher will accurately understand the powerful differences between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2–4, distinctions that are essential for understanding the meaning of the passages? And even if all these teachers do understand, how will they ensure that 5- and 6-year-olds are learning what is intended to be taught?

When these kindergartners ask questions about Genesis, how will their teachers answer? Many teachers have doubtless learned Genesis through their own Sunday school experiences. If my experience teaching the Garden of Eden story to college kids is typical, most of these teachers will have learned it incorrectly, as I once did. But it’s a snake in the garden, not Satan. The word sin does not appear in the passage, let alone original sin, nor is it clear from the passage itself that, as Milton claims in Paradise Lost, human disobedience is the problem. Having taught the passage many times, I have had to tell college students repeatedly that Jesus is decidedly not in the Garden of Eden. Teachers will have to follow lesson plans to the letter (because their district superintendents wanted the funding that came only with the curriculum), dodging all student questions and killing curiosity. Or, if they hope to actually engage with their students, they will have to rely on their own devotional traditions, smuggling in, whether they know it or not, particularly Christian (or possibly, but statistically less likely, Jewish or Muslim) beliefs.

I cannot imagine why those who identify as members of faith traditions would want public-school teachers thrusting their arms into hives and swarms of stinging bees, in the hopes of gathering what honey? The material is inherently challenging. It’s torn from context. There’s no evidence that teachers are being equipped to succeed, and no evidence that students will take from the Bible passages the lessons the teachers—or communities of faith—hope they will.

It seems suspiciously as if the real goal of including Bible passages in public-school curricula is not so that students can successfully show that they have learned something, but that the boards of education can successfully show those who keep pressuring them that they—the school boards—are as bendable as can be. The children themselves are pawns. The teachers are clearly pawns. And the Bible itself is being made into a pawn, which is to me a great sorrow.

It turns out I have found my outrage. If the Texas curriculum-makers get to take their Jeffersonian scissors to the Bible to cut it to size for the masses, they will almost certainly leave on the cutting-room floor—they always do—the Old Testament’s clarion call for justice for migrants, orphans, and widows, and the New Testament’s pervasive and scathing indictment of wealth and of all those who make money by impoverishing others. If there were lesson plans on Job’s harsh words for pious hypocrites—or Isaiah’s harsh words or Jesus’ harsh words—maybe I could let my indignation come from the Bible itself.

Get the best of news and politics

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.

Discover more from CaveNews Times

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

![Exploring the Serene Beauty of Nature: A Reflection on [YouTube video title]](https://cavemangardens.art/storage/2024/04/114803-exploring-the-serene-beauty-of-nature-a-reflection-on-youtube-video-title-360x180.jpg)