(RNS) — Novelist Hannah Lillith Assadi is the daughter of an American Jewish mother and a Palestinian Muslim father who fled the “Nakba,” or catastrophe, of 1948, when Israel was founded and Jewish militias emptied villages of Arab residents.

In Assadi’s 2017 novel, “Sonora,” the central character, Ahlam, is half Israeli and half Palestinian, and the divide haunts her parents’ marriage. Ahlam herself is an outcast who runs away to find a life as an artist.

Assadi, 37, who lives in Brooklyn, New York, does not have immediate family in Israel or the occupied territories but has more distant relatives who have been killed in Gaza.

She has supported the idea of a binational state of Israel where Palestinian refugees are allowed the right to return. “I think that’s the solution I believed would address all the injustices since 1948,” she said.

But the Israel-Hamas war has made her doubt that such a solution is possible. “What’s changed maybe in the last few months is that I don’t know how we come back from this. I think something has irrevocably been damaged.”

In 2021, The Jerusalem Post reported that according to data from Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, there were some 85,000 intermarried couples out of Israel’s total of 1.3 million married couples, or roughly 7%. While there is no information about how many of these are Jewish-Palestinian marriages, it can be presumed given the region’s demographics that many of them are.

People of a mixed Jewish and Palestinian heritage have described their experience of the Israel-Hamas war as double grief. Not only because of the divide they feel in themselves but also because it has raised tensions among their families and friends.

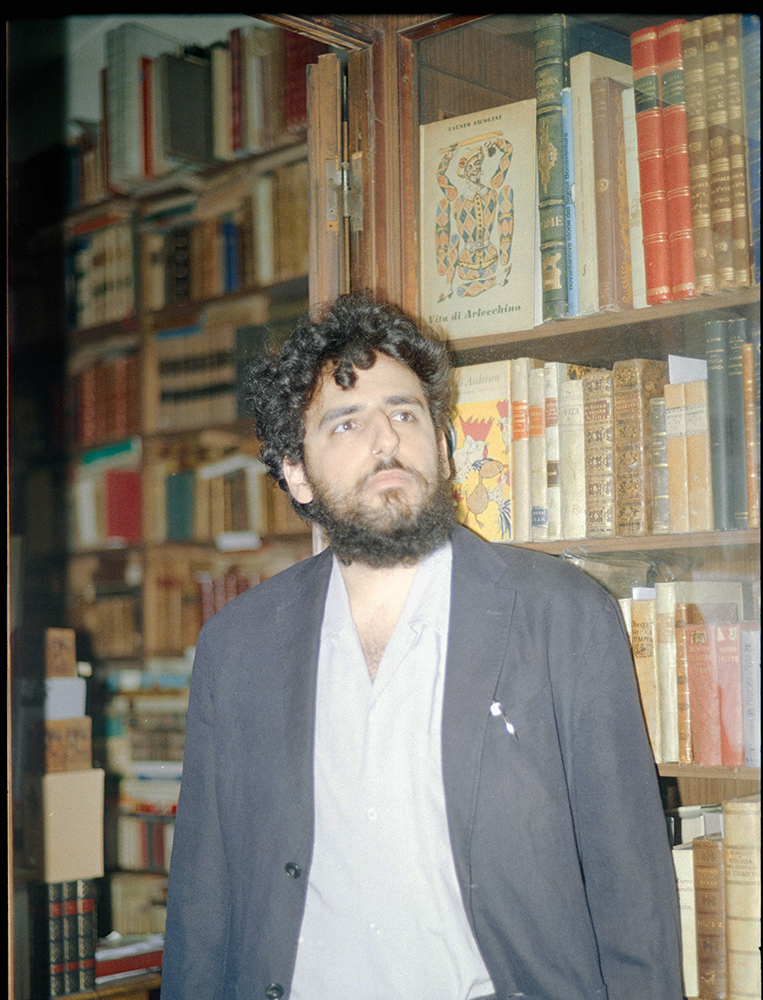

Writer Hannah Lillith Assadi. (Photo by Vera Snova)

Since the war began after the Hamas attack on southern Israel on Oct. 7, some half-Israeli and half-Palestinian or American Jewish and Palestinian writers like Assadi have written and spoken about their experiences between the two communities since the war began, as they navigate polarizing arguments among family and friends as well as their own identities.

Assadi said the war has made her Jewish relatives more aware of her support for the Palestinian cause, since she has been very vocal about it on social media. Most of Assadi’s discourse with this side of her family since Oct. 7 has been on social media.

“Nobody has canceled me in my family; I just think it’s more that there’s a certain reserve, and it would be interesting to see how things would pan out if we were in person together, which we just haven’t been.”

One difficult thing for her Jewish family to hear, Assadi said, is that her support for U.S. President Joe Biden has been diminished in the past few months due to his policies.

However, Assadi has also had some fruitful conversations with her family about the conflict. “There’s just been some very civilized disagreements with certain members of my family, over, just, op-eds passed around where I’ve just said, ‘I don’t agree with this,’ and we’ve had a very constructive dialogue about why,” she said.

But Assadi said she has lost a very dear friend, who is Jewish, over their disagreements about the conflict.

“I want to believe that if we were able to be in person together, and looking each other in the eye, it wouldn’t have been as easy for this to happen,” Assadi said.

Assadi added that this is happening to many people across diaspora communities who are Palestinians or allies of Palestinians and supporters of Israel.

Moving forward, Assadi plans to think of other ways to revisit Jewish-Palestinian identity, and the conflict, in her writing, but not immediately. “Part of the reason for that is, the ship is still in the storm! This isn’t over yet, and I don’t know where the shore is. Maybe, when there’s a cease-fire, we’re standing on the shore, and I can actually see it a little bit more clearly.”

The author and poet Amir Sommer, who grew up in Haifa and now lives in Berlin, is also navigating heightened emotions among his friends. The son of a Palestinian Muslim father and an Ashkenazi Jewish Israeli mother whose own father was Christian, Sommer, 31, was raised with all three faiths.

Writer and poet Amir Sommer. (Photo by Ella Treml)

In the latest crisis, five friends and acquaintances on both sides of the conflict were “brutally murdered,” he said, including one of his best high school friends. Sommer was so distraught that for more than two months he was unable to think about writing. Finally, in January, he expressed his grief in an article published in the Los Angeles Times, titled, “I’m Half Israeli and Half Palestinian. This War Feels as Though It’s Killing Me Twice.”

Sommer said friends on both sides of the conflict have become more hardened in their views. “Many left-wing friends from both sides have lost hope in peace (or a two-state solution) and made a swift shift towards nationalism, radicalism and militancy. Some of them are completely unaware of how different they sound,” he told RNS in an interview conducted via Google Docs.

Sommer said that while he empathizes with his friends, his commitment to seek common ground through dialogue is unwavering, and he is working to build a forum for people like him. Both the Israeli and Palestinian societies have failed to include mixed-race people, he said, and he hopes this forum will give a voice to people who “have two eyes, one for Israel and one for Palestine.”

“Gathering research and statistics has been a challenge without official sources, so I’ve been reaching out through word of mouth,” he said. “While there aren’t many mixed descendants now (only a few dozen), it’s heartening to see newborns in the last four years.”

Sommer said he is currently writing a collection of semi-autobiographical short stories titled “Disco for Peace,” which deals with the mixed-race half Israeli and half Palestinian identity of the protagonist.

Writer and journalist Mya Guarnieri, who holds both U.S. and Israeli passports, is raising two children in South Florida with her Palestinian ex-husband. Guarnieri reported in the West Bank for nearly a decade and in 2017 published “The Unchosen: The Lives of Israel’s New Others,” about the plight of asylum-seekers and migrants in Israel. Her next book, due out next year, depicts her Romeo and Juliet-like relationship with her ex-husband.

Guarnieri, whose daughter is 8 and son is 6, is raising her children to feel at ease with their varied identities. “They know that I have an Israeli passport and citizenship. They do not have Israeli citizenship, and I’ve never identified them as Israeli. My ex-husband identifies as Palestinian, and I think they identify as probably American-Palestinian, but also Jewish and Muslim. And they don’t see a conflict between those identities,” she told RNS.

She is raising them to understand all three of the major Abrahamic religions, telling them that when they are older, they can choose any religion they want.

As her ex-husband is not a practicing Muslim, she has taken charge of her children’s Islamic education, bringing them occasionally to a mosque, fasting during Ramadan and making iftar, the meal that Muslims eat when they break their daily fast.

“We talk about how in Islam, Issa, the Arabic name for Jesus, is a prophet. We talk about how in Judaism, we’re still waiting for the Messiah. And that we don’t accept Jesus as our Messiah. So we engage really deeply with Christianity as well,” Guarnieri said.

She added that there have not been conflicts in her larger family, whom she describes as “quite progressive” in their views on the conflict, while she said the children don’t speak very much to their family in the West Bank.

She said, “I want them to understand there’s no side to pick, you can be on the side of humanity.”

Discover more from CaveNews Times

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

![Exploring the Serene Beauty of Nature: A Reflection on [YouTube video title]](https://cavemangardens.art/storage/2024/04/114803-exploring-the-serene-beauty-of-nature-a-reflection-on-youtube-video-title-360x180.jpg)