“Risk Something, Sisters!”

Second-wave lesbians are often dismissed as lacking style. But their publications prove that they were artistically provocative, deeply funny, and incredibly brave.

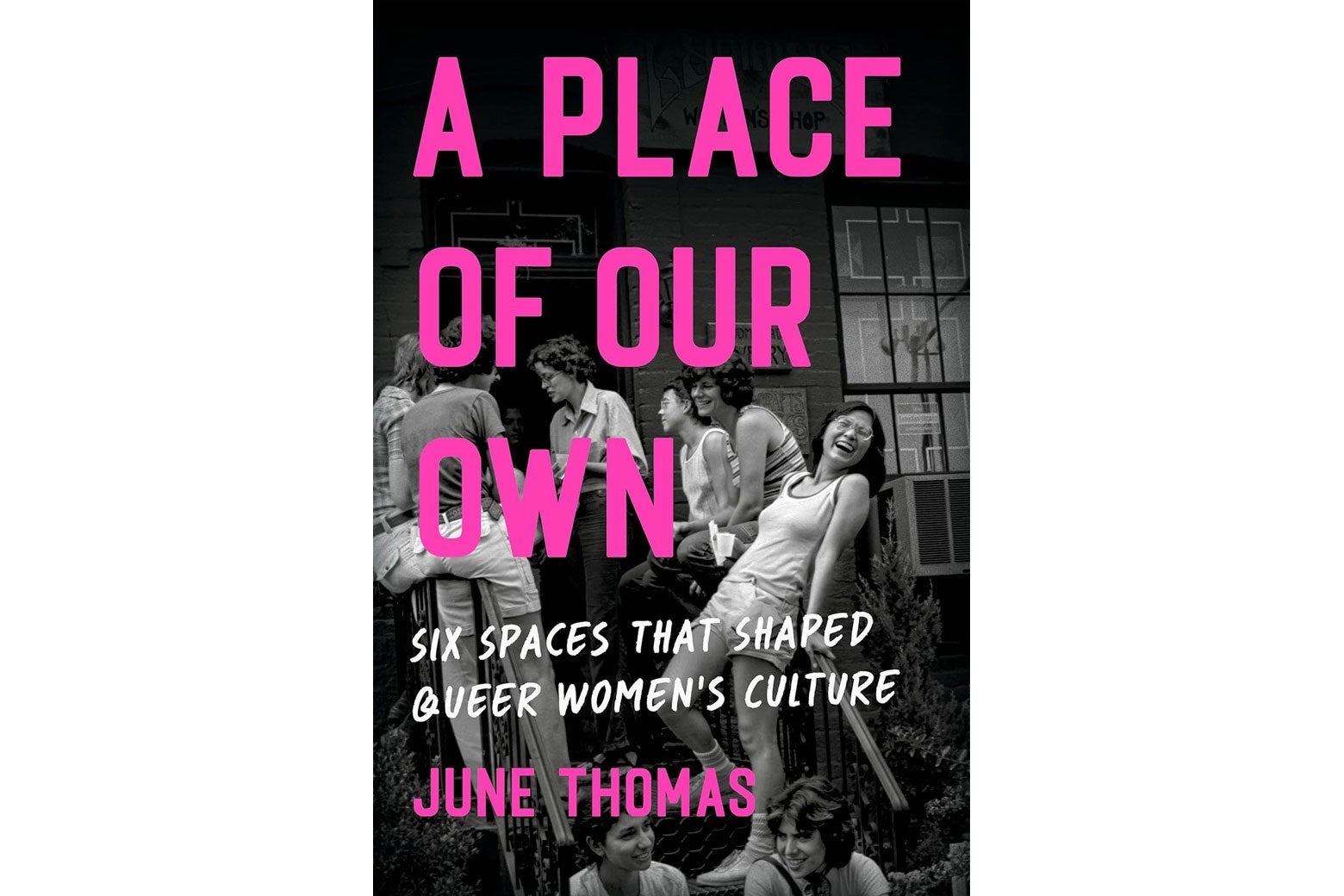

If one’s computer hard drive provides a window to the soul, mine reveals a woman with a bit of an obsession: It is stuffed to the brim with pages grabbed from feminist and lesbian-feminist magazines of the 1970s. One reason is practical—I called upon their excitable news stories and impassioned editorials when writing my new book, A Place of Our Own: Six Spaces That Shaped Queer Women’s Culture. But another is a matter of pride: These grassroots publications provide an undeniable rejoinder to two of the most enduring but comically wrongheaded ideas about second-wave feminists: that they lacked a sense of humor, and that they had no style, particularly when compared with the campy, chichi reputation of midcentury gay men.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page.

Thank you for your support.

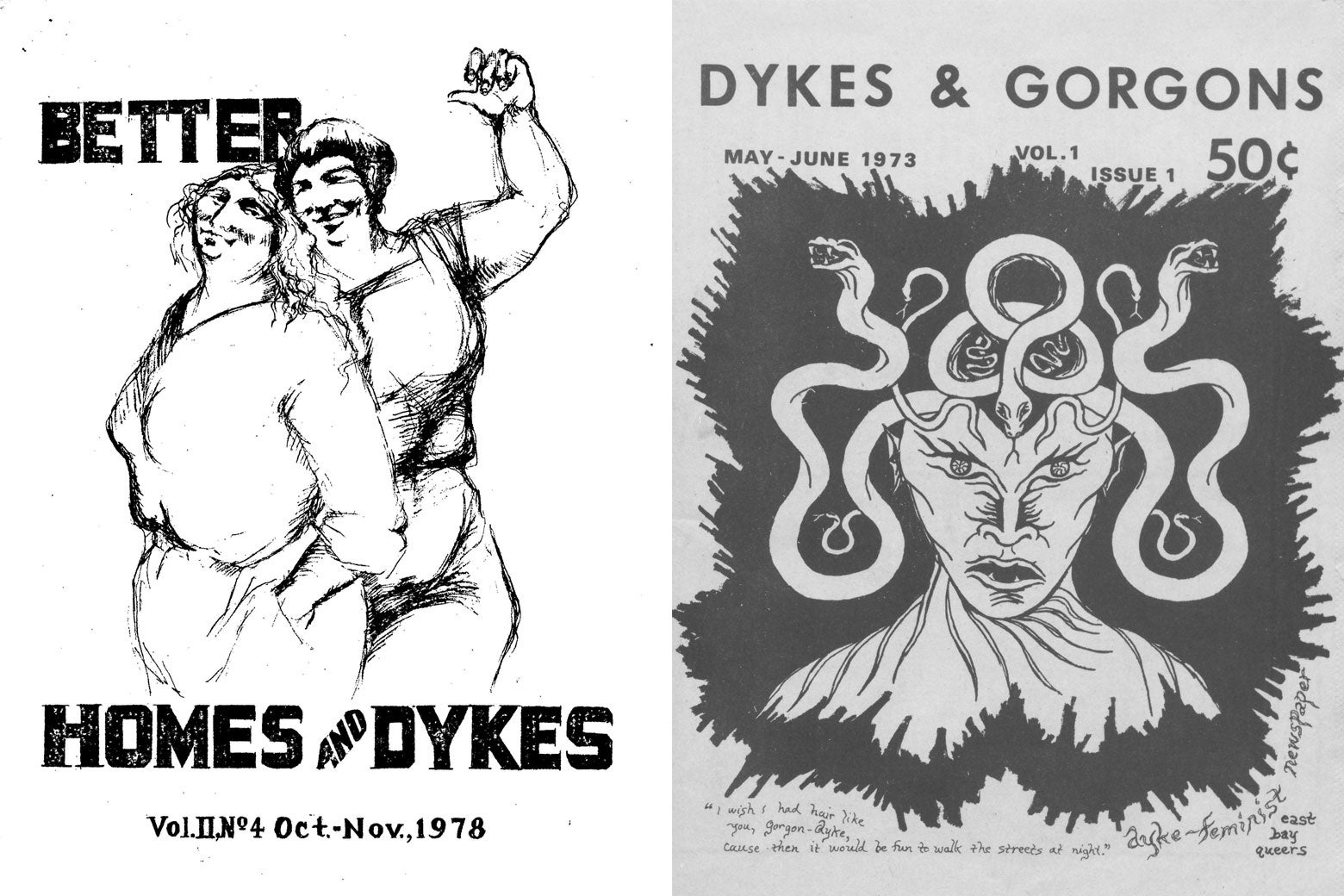

You need do no more than list the names of these publications to destroy that first notion. I put it to you that women who gave their magazines names like So’s Your Old Lady, It Ain’t Me Babe, Big Mama Rag, Off Our Backs, Better Homes and Dykes, the Leaping Lesbian, and Dykes & Gorgons were pretty darned funny, thank you very much. (Meanwhile, the Twin Cities publication Les’binformed proves that cringe comedy was, in fact, invented by lesbians.)

The Archives of Sexuality and Gender

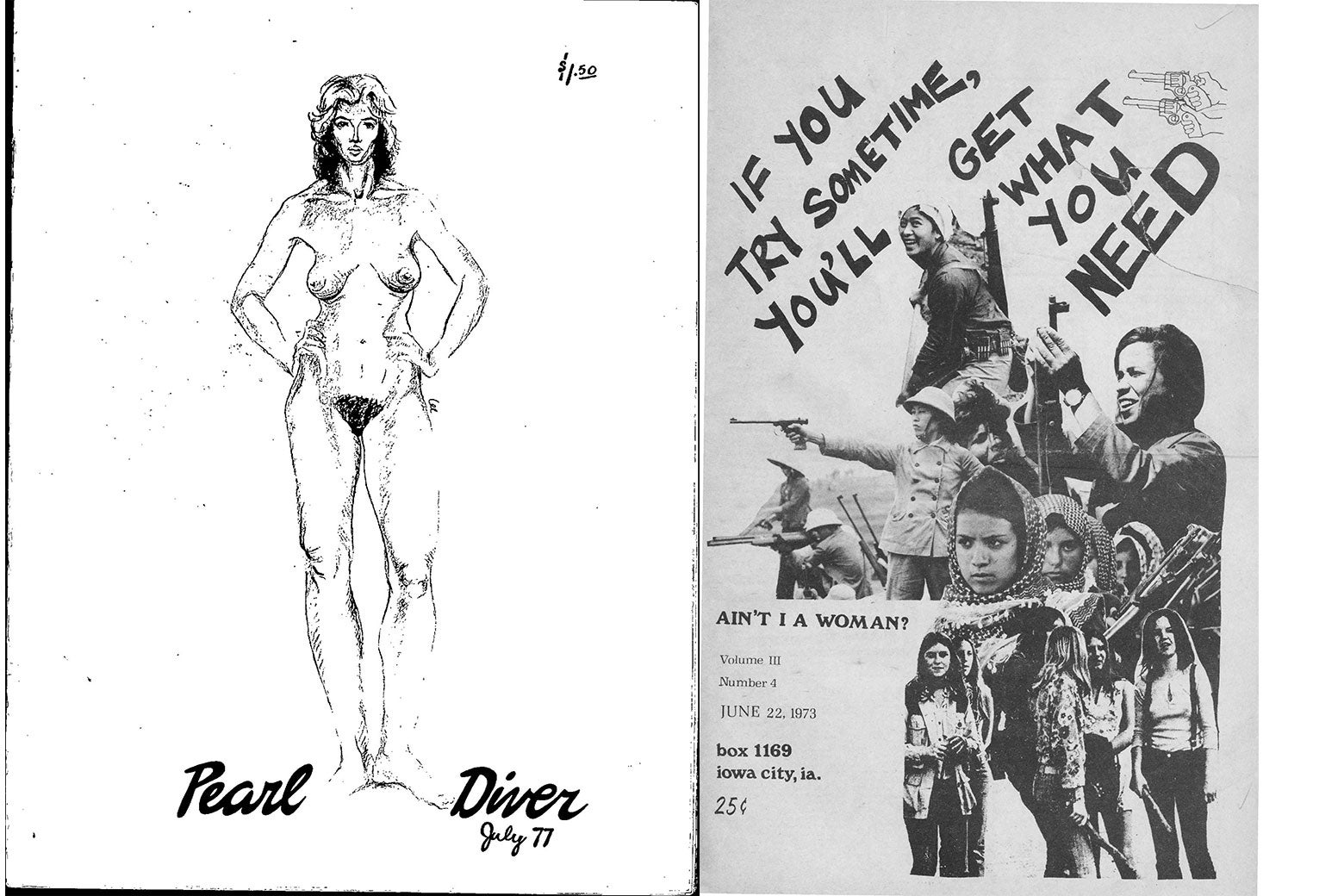

Even more striking, though, is the radical and often unsettling beauty of the covers that adorned these periodicals. Looking through the 50-year-old newsstand that is my downloads folder, it seems clear that ’70s lesbian-feminist aesthetics were raw, bold, and sometimes even chic, in spite of—or is it because of?—the shoestring budgets and inexperienced volunteer crews that shaped them.

The explosion of publications was a direct consequence of the new feminist ideas that emerged in the 1970s. Many, including Off Our Backs and It Ain’t Me Babe, had their origins in anti-war and campus-protest movements, but chauvinistic behavior by men in mixed groups quickly pushed women to focus on their own liberation and create their own magazines.

The Archives of Sexuality and Gender

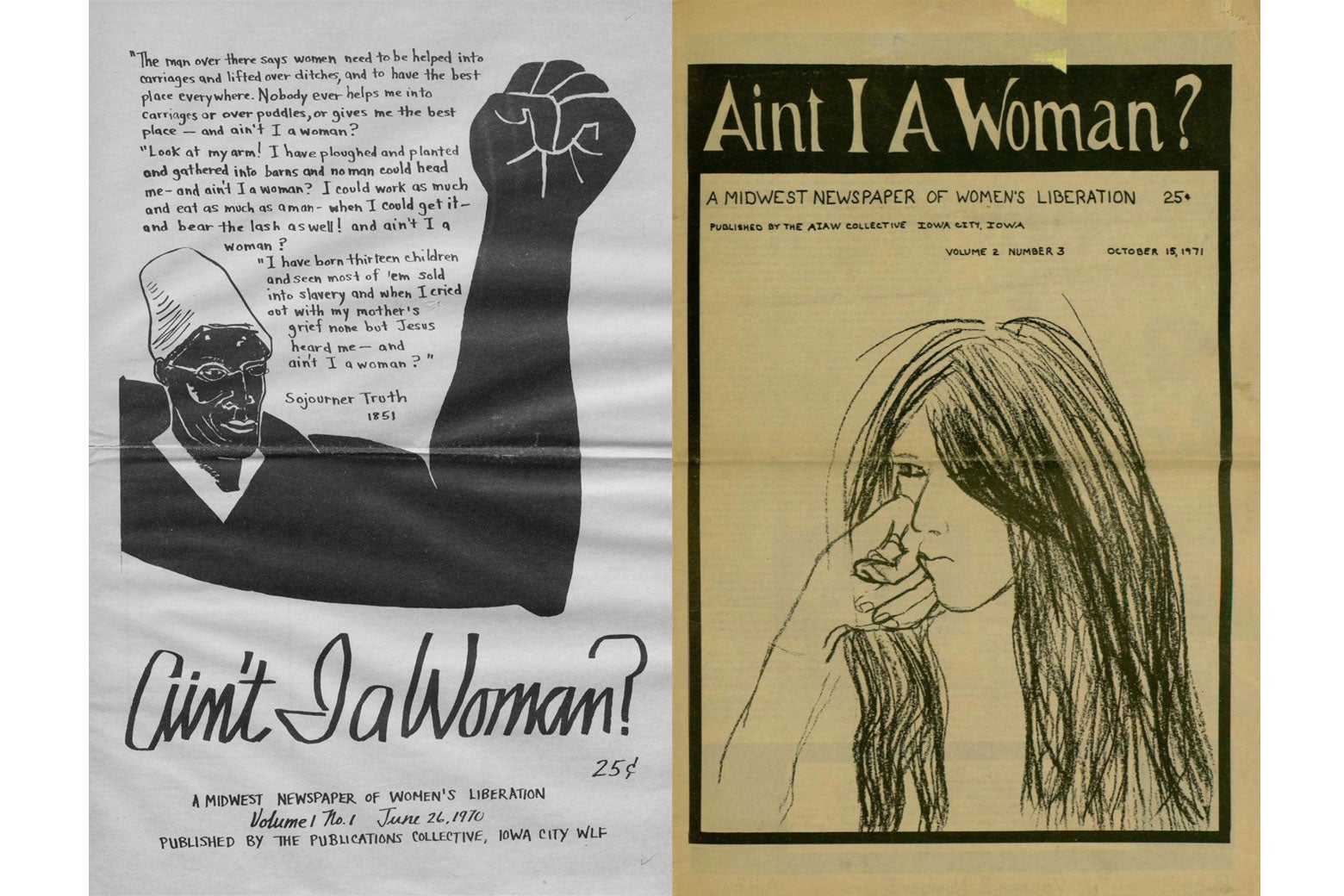

In the first issue of Iowa City’s Ain’t I a Woman?, which appeared in June 1970, the 14-woman collective wrote, “We need to develop all kinds of abilities and know we have not been able to do this working jointly with men. We would tend to do mostly routine shit work even if this wasn’t imposed on us.” An article summarized the negative self-talk the collective was determined to help contributors overcome, including “I can’t write” and “I don’t know how to draw and maybe no one else does either.” The covers of the first two issues featured sketches of Sojourner Truth, along with a hand-lettered excerpt from her 1851 speech that was the source of the magazine’s name. But the DIY ethic that informed this and similar publications meant this consistency was short-lived. As collective members came and went, and as artists with differing levels of experience and skill contributed their work, one month’s exquisite cover might be followed by a … less successful effort. The collective was more interested in building confidence and changing lives than maximizing newsstand sales. The cover of the Oct. 15, 1971, issue was drawn by a 12-year-old girl.

Few of the women who worked on these magazines had a background in journalism or graphic design. According to 1973’s New Woman’s Survival Catalog, the crew that put out Denver’s Big Mama Rag included “a bus driver, a painter, a mother of two, a legal secretary, an astrologer, a pre-med student, a welder, a draftsperson, a past treasurer of the National Honor Society, and an ex-nun.”

The Archives of Sexuality and Gender

It Ain’t Me Babe, which burst out of Berkeley, California, in 1970, managed to squeeze decades of outrage into 17 issues published over the course of one year. Even its name, a feminist twist on a Bob Dylan lyric, thumbed its nose at the icons of the day. (Dylan’s original line, “To gather flowers constantly/ and to come each time you call/ a lover for your life and nothing more./ But it ain’t me, babe” became “To subsume me in your shadow/ to come each time you call/ a lover for your life and nothing more/ it ain’t me babe.”) The volunteer staff sneakily typed up articles on university office equipment, thanks to a friend who allowed them into the sociology department after hours. They laid out the issues in staffers’ homes, and as co-founder Bonnie Eisenberg later noted, “Headlines were sometimes hand-lettered, columns were sometimes crooked … but the look of the paper improved greatly as time went on.” Eisenberg credited a good deal of that glow-up to the arrival of cartoonist Trina Robbins, who contributed several comic strips and covers, including Issue 4’s image of secretary Belinda Berkeley, who “wanted to be a writer but her old man has talked her into taking a typing job so he could write his novel.” The Babe’s most famous cover was Issue 8’s, featuring a stars-and-stripes-painted papier-mâché penis that had been dumped into the trash. The San Francisco Chronicle’s Herb Caen mentioned the striking photograph in his column, along with the paper’s address, which led to a circulation boost.

The Archives of Sexuality and Gender

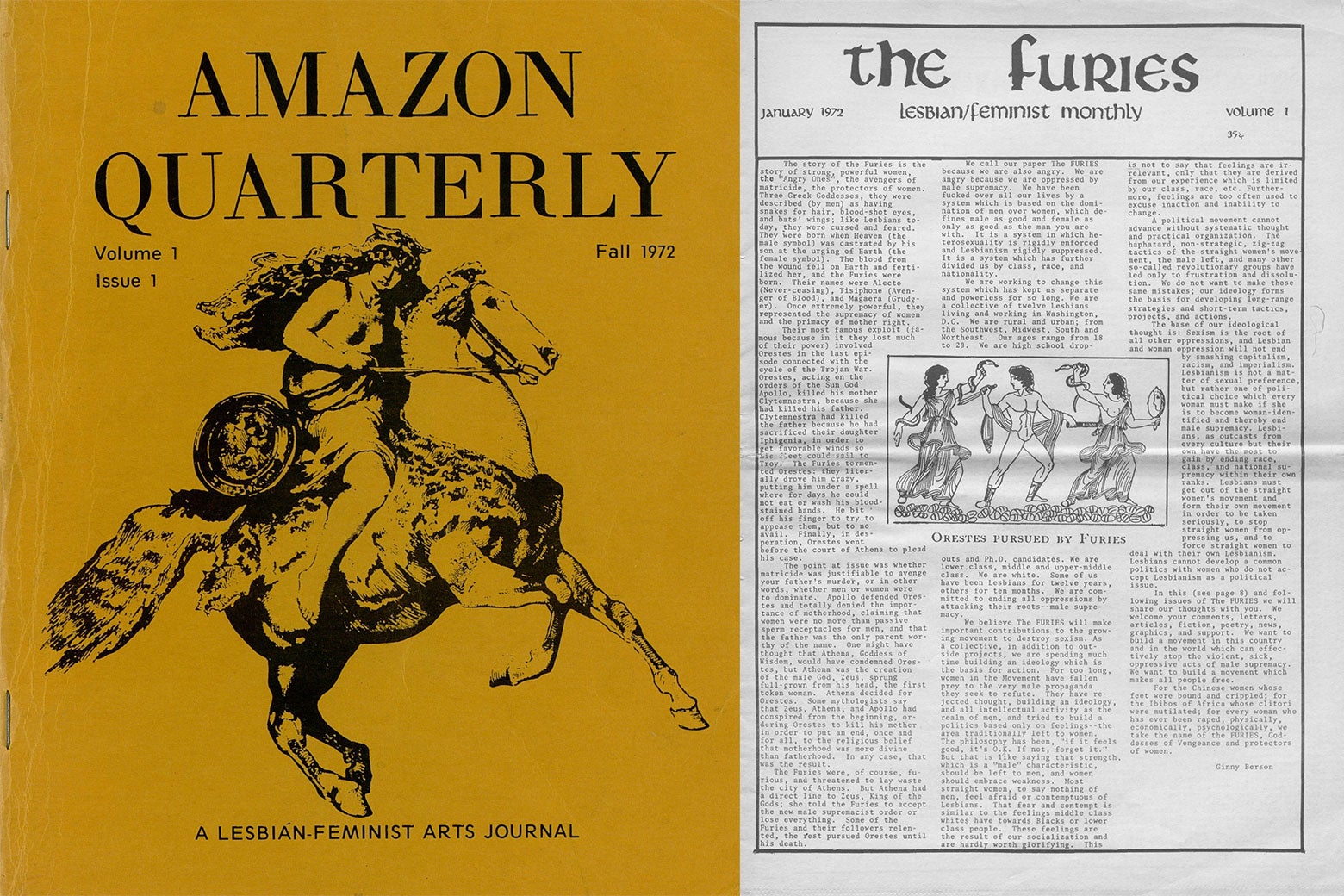

A movement driven by new ideas was also inspired by imagery from the ancient past. Washington’s lesbian-separatist collective the Furies took its name, and the title of its publication, from the avenging Greek goddesses, because they, too, were “angry because we are oppressed by male supremacy.” The cover of the first issue, which appeared in January 1972, featured a naked man and two (mostly) clothed women—Orestes being pursued by two of the Furies—but the collective consciously avoided graphics that depicted female nudity because they wanted to smash the notion that lesbianism was a purely sexual matter.

Later that same year, on the West Coast, Gina Covina and Laurel Galana started Amazon Quarterly in an effort to find other lesbian-feminist artists. Or as they put it, “We would spread the tantalizing bait of Amazon Quarterly across the waters and see who came to nibble.” While Ain’t I a Woman? promised to “print without editing any laid-out page from a Midwest (New Mexico thru Ohio) Women’s Liberation group,” Amazon Quarterly was selective. In the inaugural issue, the editors wrote, “We simply want the best of communication from lesbians who are consciously exploring new patterns in their lives. … Risk something, sisters.” Standards weren’t the same as elitism, though. Over multiple pages in two issues of Volume 2, Galana painstakingly instructed readers on how to make a magazine, including typesetting, layout, and working with a print shop. The first and second issues of Amazon Quarterly featured the exact same cover image printed on different colored backgrounds (to be fair, she was a bad-ass Amazon astride a fine steed).

The Archives of Sexuality and Gender

Who knows what heights feminist publishing aesthetics might have reached were it not for restrictions imposed by male-owned and -operated print shops. Nudity was rare but not unknown, and while printers sometimes refused to reproduce images they considered pornographic and that risked running afoul of obscenity laws, they were just as likely to balk at basic medical information. A note in the eight-page November 1971 issue of Ain’t I a Woman? declared, “This was to be a twelve page paper, with four pages of medical self-help material on menstrual extraction. However, we couldn’t get them printed.” (The offending content also included instructional photographs on cervical and breast self-examination.) In November 1970, collective members from Washington-based Off Our Backs had to schlep to New York to get an early issue printed when the regular shop refused a satirical center-spread ad for “Butterballs,” a genital deodorant for men.

Half a century later, one recurring cover topic does seem genuinely shocking: images of women holding guns. As the authors of a 2013 article in the feminist journal Frontiers observed, these images “demonstrate how palpable and immediate revolution was for many feminists. … This was a time when people believed that armed struggle was a viable way to make change.”

Fifty years on, it’s hard to track down much information about the women who created these publications—stories and graphics were often anonymous, pseudonymous, or credited by first name only—but the magazines they left behind are lasting expressions of their rage, curiosity, and excitement. The publications’ influence on the wider culture is debatable; most had limited and usually regional distribution, but unlike today’s easily deleted web outlets, they live on in a few analog archives, my poor hard drive, and now in your imagination—a record of a unique taste and aesthetic sensibility that couldn’t be bought or taught. It might not be as celebrated as the boys’, but it should be: Lesbians had—and have—incredible style.

Discover more from CaveNews Times

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

![[Highlight] Steph Curry hits the step back three and tells the Mavs it’s time to go Night Night!](https://cavemangardens.art/storage/2024/11/174867-highlight-steph-curry-hits-the-step-back-three-and-tells-the-mavs-its-time-to-go-night-night-360x180.jpg)

![Exploring the Serene Beauty of Nature: A Reflection on [YouTube video title]](https://cavemangardens.art/storage/2024/04/114803-exploring-the-serene-beauty-of-nature-a-reflection-on-youtube-video-title-360x180.jpg)