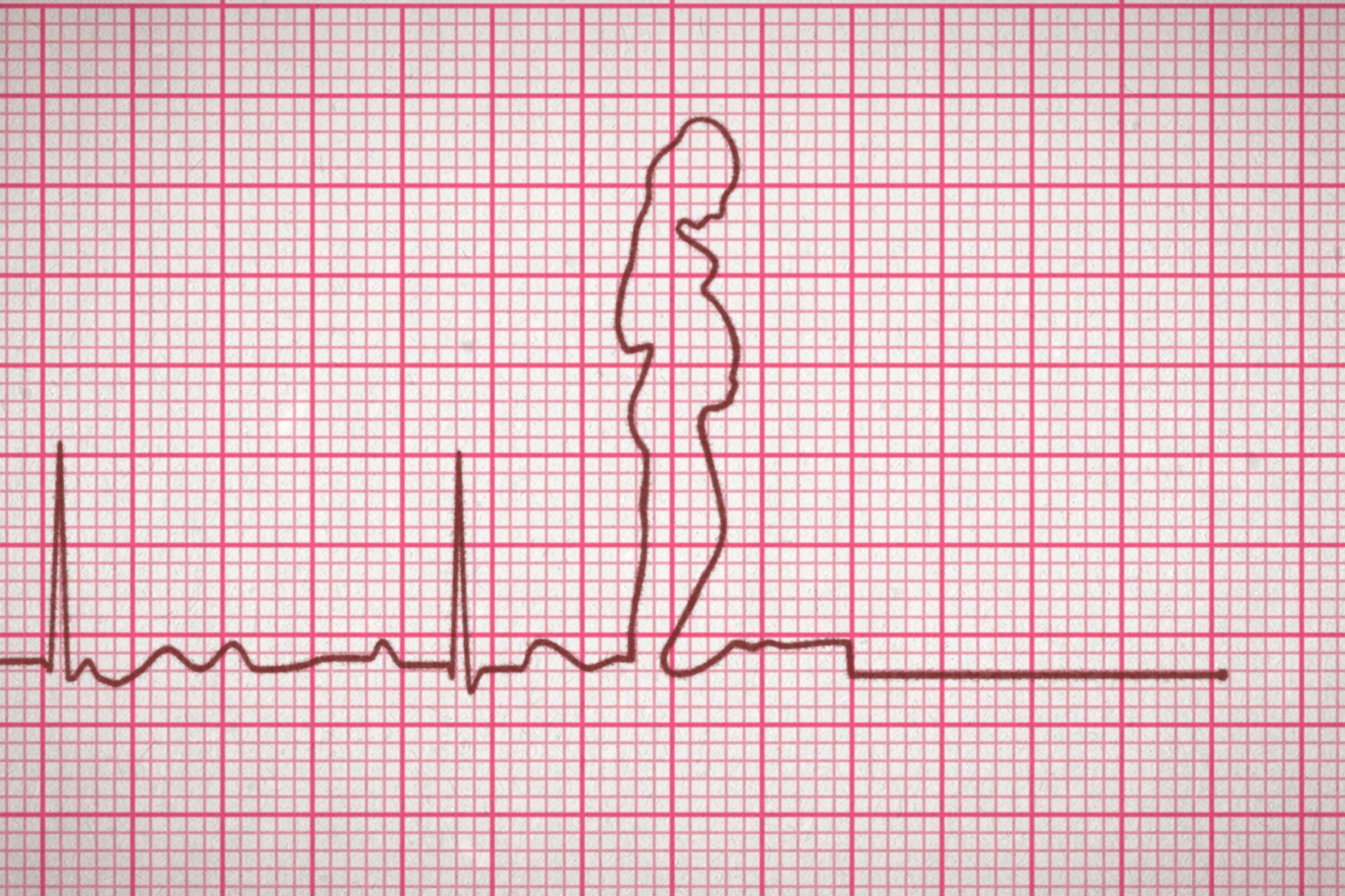

The latest abortion struggle is between a federal law meant to keep patients safe and a state effort to outlaw abortion in all but the rarest circumstances.

This week, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments in a dispute over whether states can decline to abide by the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. EMTALA is a federal law requiring stabilizing care for all ER patients, including abortion care, even if it conflicts with a state’s own stricter abortion rules. Moyle v. United States consolidates two cases—Idaho v. United States and Moyle v. United States.

The issue is reasonably simple: EMTALA has been broadly understood to cover—and in 2022 the Biden administration clarified that it did indeed cover—the need to perform stabilizing abortion care on patients for whom it is the medically indicated treatment to resolve a medical emergency. The state of Idaho’s anti-abortion law allows for an abortion when “necessary to prevent the death of the pregnant woman,” but not when it might MERELY cause disability or seriously bodily harm. The Biden administration sued Idaho, alleging that the state’s abortion ban conflicts with EMTALA and that federal law trumps Idaho law. That’s Supremacy Clause 101: When a federal law conflicts with a state law, the federal law preempts the state law. (It’s also called preemption.) But Idaho contends that THIS state law should absolutely trump the federal law. When a federal district court ruled in 2022 that Idaho’s abortion ban cannot trump EMTALA if a pregnant patient has a medical emergency that requires an abortion, the U.S. Supreme Court stepped in and put that order on hold.

Earlier this month on the Amicus podcast, Dahlia Lithwick spoke to emergency medicine physician Dara Kass about the health care that happens in the gap between the federal requirement for stabilizing care and the local laws in Idaho and other states that have enacted near-total abortion bans post-Dobbs. Their conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity. You can listen to the whole episode here.

Dahlia Lithwick: So, EMTALA requires that if an individual comes to a hospital and the hospital determines that they have an emergency medical condition, they must “stabilize the condition,” and then it defines the term “emergency medical condition” to include things that put a patient’s health in serious jeopardy, threatens serious harm to a patient’s bodily functions, any bodily organ. Mental health is also included. Can you just walk us through what range of things go into that description of what an emergency is?

Dara Kass: It’s actually much more simple in practice than it is on that list, and that’s why the lists tend not to be helpful to doctors. So somebody comes to my emergency department and I immediately assess them for an emergency. That will be things like checking their vital signs, making sure that if they’re bleeding, they’re not bleeding in a way that would threaten a need for transfusion immediately or that it wouldn’t increase the rate of bleeding. It may be things like, if they are at risk for self-harm and I discharge them, are they at risk to harm themselves over the next 24 hours? Those are all under the umbrella of EMTALA.

When I see somebody immediately in an emergency department, I’m making sure that they don’t need an intervention right there that will prevent them from getting worse. We can’t fix everything, but we have an arsenal of options—treatments, interventions, medications, consultants. We do everything we can right there, before anything else, to make sure that the patient is OK for now, and we don’t stop until they are as OK as we can make them. That’s what EMTALA protects, and trying to parse out what’s allowable treatment under that protection vs. what is not allowable has never been done. We have never seen legislators look at the idea of intervening to prevent harm to somebody as then limited in its practice, not for medical knowledge, not for changes in safety and efficacy, but only because legislation has decided that that procedure is only allowable in certain circumstances.

EMTALA protections are broader than the exception under the state law in Idaho, and it’s really frustrating to hear lawyers argue about this idea of “life of the mother” as being predictable. I spend every day in an emergency room when I have patients in front of me who are not doing well, or even who have the potential to not do well. We’re trying to prevent that window opening where, within 24 hours, somebody could unfortunately die. Having to wait until I’m in that window to intervene is dangerous for people. The risks of waiting until you’re at the brink of death, even if you don’t die, will have consequences to your life and future, to your fertility and organs and a lot of other things.

It’s not harmless to wait until the brink of death to intervene. And in emergency medicine, we’ve always known that. That is literally the gray area we’re fighting in right now.

I’m sitting here, wanting to parse the space between “organ damage” and “necessary to prevent the death of the pregnant woman”—that’s the Idaho language—and you’re like, “Dahlia! Parsing words is not my job. It’s your job. My job is, if somebody is going septic or at risk of a heart attack, I don’t wait till they’re having a heart attack.” That’s what you’re telling me.

I mean, we’ve seen this. Someone goes to the ER with chest pain, right? They are not having a heart attack. Often, they still see the cardiologist. They still go to the cardiac cath lab to figure out if they are at risk of a heart attack. We intervene early to make sure they don’t have that heart attack, right? If we only wait until heart attacks happen to fix people’s clots in their heart, people would do worse.

In pregnancy, there’s a really descriptive example that makes a lot of sense to people, and it’s ectopic pregnancy. From the time you get pregnant to the time that I can see an ectopic pregnancy, which is a pregnancy outside of the uterus, in the wrong place on ultrasound, and I can see what would be an embryo forming in the wrong place, and sometimes the heartbeat—there’s a timeline. There are different pieces of information. It’s a movie. When I see you in the ER, I only get a snapshot. I get a still image. When you come to an ER in a state that doesn’t have restrictions on abortion access or you’re in a hospital that doesn’t have any restrictions, I can offer you treatments earlier in that movie based on what you want.

So, for example, you’re pregnant. Whether the pregnancy is desired or undesired is not relevant to the medical care we’re talking about right now—you’re pregnant. You don’t have a pregnancy in the correct place. I don’t see a pregnancy in your uterus. Your hormone levels are rising and you have abdominal pain. I can offer you the treatment, which would be to terminate this pregnancy medically, which would mean a shot, and we can follow your hormone levels down and then you can try to get pregnant again if that’s what you want. Or I can wait 24 hours, we can repeat your hormone levels and look again and see if the pregnancy is in the correct place or not in the correct place, and we can intervene.

That waiting is not risk-free. That waiting means that I could find the pregnancy in the tube in the wrong place but I could also find a heartbeat. And if I do, the treatment is different. The treatment is no longer a shot. The treatment is now surgery, and that surgery often removes your tube, and that changes your future fertility. And if you don’t come back within 48 hours and you still have that embryo in the wrong place, now you’re at risk of what we call rupture. And many people have heard stories of people who have been sent home from the emergency department waiting for that evidence, that irrefutable, legally verifiable evidence that it is actually an ectopic pregnancy that you’re treating, that there is no doubt, criminally, that you could be charged for ending early what could potentially be a viable pregnancy.

Doctors are feeling like they have to wait until that irrefutable evidence is in place, rather than offering intervention earlier when we are 98 percent sure that it’s going to end up in that place. And we’re seeing cases of people having rupture of their tubes, losing tubes—the anxiety alone, to know that you might have an ectopic pregnancy and they’re not treating you today but you have to come back in two days, is something we never talk about. And there are harms. Under EMTALA, the protection is to do what you need to do to stabilize somebody across all options you have. And yet we see, all the time, doctors changing their clinical practice to meet the legal mandates that they’re living in.

Up until Dobbs, and states starting to pass these much more constricted abortion laws, how did you make these calls? Until Dobbs, it was not a legal question, right? You just made the best judgment about what was required?

None of us can say that abortion access was accessible to all Americans before Dobbs. There were plenty of restrictions in place, but what we had were our foundational protections that in an emergency you weren’t going to go to jail. That’s what we’re talking about here. Physicians were not worried about being criminalized. Physicians weren’t modifying their practice because a prosecutor would come after them for care that saved someone’s life.

One of the claims in the state briefing is that EMTALA requires hospitals to offer stabilizing care to the unborn child. What they are saying is, if there’s a medical emergency that endangers the fetus’s life, that means that EMTALA is kind of at war with itself because it includes a mandate that you have to protect fetal life. Can you talk about both that argument, but also just what this creeping notion of embryonic children, fetal personhood, does to the practice of emergency medicine?

The bottom line is that EMTALA’s “and Labor Act” part was about active labor. It was about the protection of a baby being born. Before, people were coming to hospitals who had had no prenatal care, they were in labor, and the private hospital was saying “You’re going to deliver at the public hospital,” and they would transfer them in active labor.

Today, for each person who comes to an emergency department in active labor, I have to check to make sure that they’re not going to deliver in the elevator up to labor and delivery. This was included in EMTALA. This was the part of pregnancy we were talking about. Active labor: delivery of a fully gestated person who’s coming out of the womb, viable, at the end of pregnancy. That is not the same as a life-threatening emergency for a pregnant person.

Previability, we have a very specific practice in emergency medicine: To save the baby, you save the life of the mother. If somebody is pregnant and they’re 16 weeks pregnant, you save the mother. That is how you save the pregnancy. It’s always been our practice.

If, in certain circumstances, the mother can’t survive and the pregnancy is past viability, we would do an emergency C-section. We would deliver that baby as fast as we can past a certain gestational limit. There are already protections in place to prioritize the life of the unborn, if you will, that are viable in an emergency. What Idaho is infusing into this is saying, Actually we’re going to prioritize the 7-week embryo over the mother who’s hemorrhaging. Because in some world that I have never been in, in all of my practice of emergency medicine, this law says prioritizing a 7-week embryo will do something for the viability and future of that embryo. There is no future for that embryo if the mother is not alive.

It’s an absurd premise to say that there’s actually a conflict existing in EMTALA. We’re going to hear a lot in these oral arguments about that possibility. And it isn’t real. It just isn’t.

Discover more from CaveNews Times

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

![Exploring the Serene Beauty of Nature: A Reflection on [YouTube video title]](https://cavemangardens.art/storage/2024/04/114803-exploring-the-serene-beauty-of-nature-a-reflection-on-youtube-video-title-360x180.jpg)