Time is both an essential form of measurement that rules our day-to-day lives and a concept that no one quite understands. From the ultrafast zeptosecond to the billions of years that the universe has been in existence, we can easily measure time’s passage. Yet some scientists question whether it is even fundamentally real.

While the concept of time can feel impossible to capture, that hasn’t stopped artist Lia Halloran from trying. Many of her projects tackle how scale and time shift our perception of reality. In her 2022 piece Double Horizon, a 3-channel video installation piece, she projected divergent but closely related images of Los Angeles from a series of repeated flights she made over the city as she learned to fly. In her 2008 work Dark Skate, she skateboarded at night through different venues in Los Angeles, using light to draw an ephemeral line through a series of photographs.

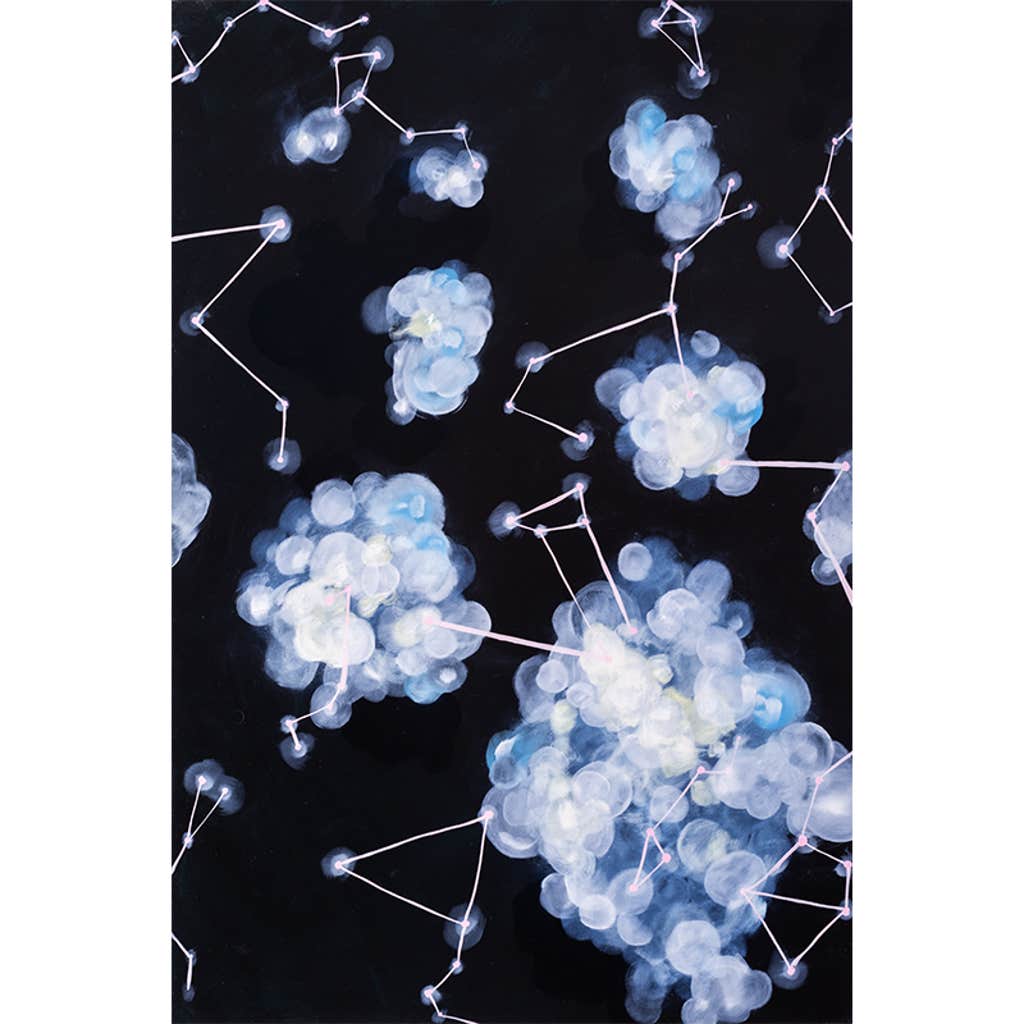

This fall, Halloran has two new exhibits that are part of an expansive art event taking place across Southern California and organized by the Getty, called PST ART: Art & Science Collide. One of those exhibits is a series of oil paintings called Night Watch, which attempts to examine how machines and tools might symbolize the natural passage of time. Another is You, Me, and Infinity, a single work that combines painting and cyanotype—a print made by exposing a UV-sensitive chemical-coated paper to sunlight—to visualize eight layers of scale, from her own growing children to gravitational waves to vacuum fluctuations at the moment of the Big Bang. I spoke with Halloran about using time as a tool to make art and what inspires her.

In your new collection of paintings called Night Watch, what are you trying to say about time?

I’ve been toying with the notion of calling them “time landscapes.” In many of the pieces, you’ll see something is changing, which means it’s going from one state to the other, whether that’s expanding, contracting, moving. In one, you can see something that references some kind of horizon. It’s not a solid depiction of a mountain or ice, but it absolutely could be. The pieces underneath the horizon are a reference to a crystalline form that’s growing because I was thinking “What’s another earth-bound way that we can reference these long expanses of time?”

Another set basically represents the seasons. There are four of them that rotate through our year. I’m fascinated by how our body itself understands time on larger scales. I really want to invite the viewer to a sense of awe and let them take it from there in a different direction. Even the title itself evokes the viewer’s participation. It’s not about what’s out there, it’s about your observation and perception of what’s out there.

Where did the ideas for Night Watch come from?

I had been thinking a lot about the way that technology mediates our understanding of things. I took my students on a field trip to Mount Wilson Observatory, which is something that I do often. I teach a course called “The Intersection of Art and Science” at Chapman University, and it’s part of the course. There’s something so magical about being on these telescopes. It feels like a loving act of trying to reach out to something. I write notes to myself about my own work, and I was thinking of [telescopes] as machines of longing. Even our understanding of these senses of time or measurement are really mediated through technology. It was actually through that thinking of how technology mediates the embodiment of our experience that I came to make this series. The first pieces that I made were based on star trails from this night at Mount Wilson Observatory.

The other project commissioned for PST ART, You, Me, and Infinity, is a large-scale piece that melds cyanotype and paint, building on your past work in cyanotypes and exploring different concepts of scale. What role does time play in this medium?

Cyanotypes not only just use astronomy to make them—we’re using the power of the sun instead of the power of a dark room—but it is based on where the Earth is in relation to the sun in the season. So, there is an element of time, but it’s not as simple as you probably think. I can only make them between June and late September because the angle of the sun changes so drastically in the sky. Starting in the fall, it starts to angle down, and therefore the exposure times of the cyanotypes start changing so drastically that it becomes nearly impossible to get the right print with the right exposure time.

But I wanted to do something that anchored these levels of scale to something that was very personal. And so I enlisted my two young children, who are 3 and 6. And in the actual piece, they just literally lay down on the negative. We’re so fascinated with the changing scale of our bodies in childhood. It’s just inherent to what childhood is, right? Even my wife and I, every week, are like, “Is he getting bigger?” So the piece itself draws from different archival or historic moments in science, but it also has very personal gestures.

I was thinking of telescopes as machines of longing.

Where do you find inspiration?

I am just very fascinated and curious about the natural world. But I also want to be careful not to put science on a pedestal and challenge the nature of discovery and even our own personal narratives and experiences in that lineage.

There’s this 1977 film that was influential for me called The Powers of 10 by Charles and Ray Eames. It starts with this man who’s asleep on a picnic blanket. It goes out into the universe, and then it goes down into the small scale of his cells. The reason I loved it so much was because it anchored the body. I think that’s why we’re passionate about things, why we’re curious about things, because science, as an embodied experience, is an amazing invitation.

As an associate professor and chair of the art department at Chapman University, what role do you think art can play in science outreach and education?

As we exist in our society, we’re all consumers of interdisciplinary culture. We are watching the election, but we’re also fascinated with the discovery of gravitational waves, or what Beyoncé’s next album is. Those things are simultaneously exciting, why can’t they exist in one space? As a teacher, the first class I developed was called “The Intersection of Art and Science” and was a partnership with the Jet Propulsion Lab. My students would visit, and they made work about current NASA missions.

I love the conversations about what art and science have to do with one another. Most everyone is like, “everything.” There are so many overlaps. But if there’s one thing that both artists and scientists are all thinking about, it’s the nature of scale. The scale of time, the scale of distance, the scale of size, the scale of measurement. I had a microbiology student who was doing surgeries on the reproductive organs of fruit flies, using these crazy microscopes, doing testicular surgery. How can human fingers even do that?

You published a book with physicist and Nobel laureate Kip Thorne last year, The Warped Side of Our Universe: An Odyssey Through Black Holes, Wormholes, Time Travel, and Gravitational Waves, which took an extraordinary amount of time to complete—more than a decade—and I imagine, had you thinking about time on a whole new cosmic level. How did that affect your artistic process?

We were looking to make a book that didn’t exist before that would sort of transport the viewer. It was very, very iterative. And that’s because Kip would come draw on top of my paintings. It was like the paintings drove the words, in poetry and prose, just as much as the prose drove the paintings. The book is really a representation of a conversation.

Those paintings are singularly very different than anything in my studio practice, because I knew that [the book] was for a wide audience. Kip wrote in poetic prose, so I wanted the paintings to have that elegance to them that you could tell they’re painted so simply, but somehow you look at it and it could not be any other way.

What’s next?

It takes me a very, very long time to think of a project. But I made this series 12 years ago that was also looking at this notion of time. I was thinking about the classification of the natural world in two forms, one the personal and one the scientific. And what better form to lean on than the periodic table of elements? And so I made this piece, which was complete in and of itself, but I really thought of as a draft. It’s a combination of the elements merged with people who were in my life. I photographed friends, ex-girlfriends, like an intimate catalog of my world. I always felt there was more there, so the next thing I want to do draws from the discoveries in Los Angeles that relate to the periodic table. That would involve tapping into some of the fantastic institutions, the Getty Research Center, The Huntington, the collection at Mount Wilson. There’s such an incredible wealth to mine from that I’m interested in doing an expansive research-focused project. ![]()

Lia Halloran’s Night Watch is on display at Luis de Jesus Los Angeles from November 9 through December 21. You, Me, and Infinity can be viewed in Caltech’s Dabney Lounge through December 15.

Lead image: Cycle, 2023, by Lia Halloran. Oil on panel, 36 x 36 inches. Photo by Adam Ottke.

-

Katie Neith

Posted on

Katie Neith is a science writer and editor based in Los Angeles.

Get the Nautilus newsletter

Cutting-edge science, unraveled by the very brightest living thinkers.

Discover more from CaveNews Times

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

![Exploring the Serene Beauty of Nature: A Reflection on [YouTube video title]](https://cavemangardens.art/storage/2024/04/114803-exploring-the-serene-beauty-of-nature-a-reflection-on-youtube-video-title-360x180.jpg)