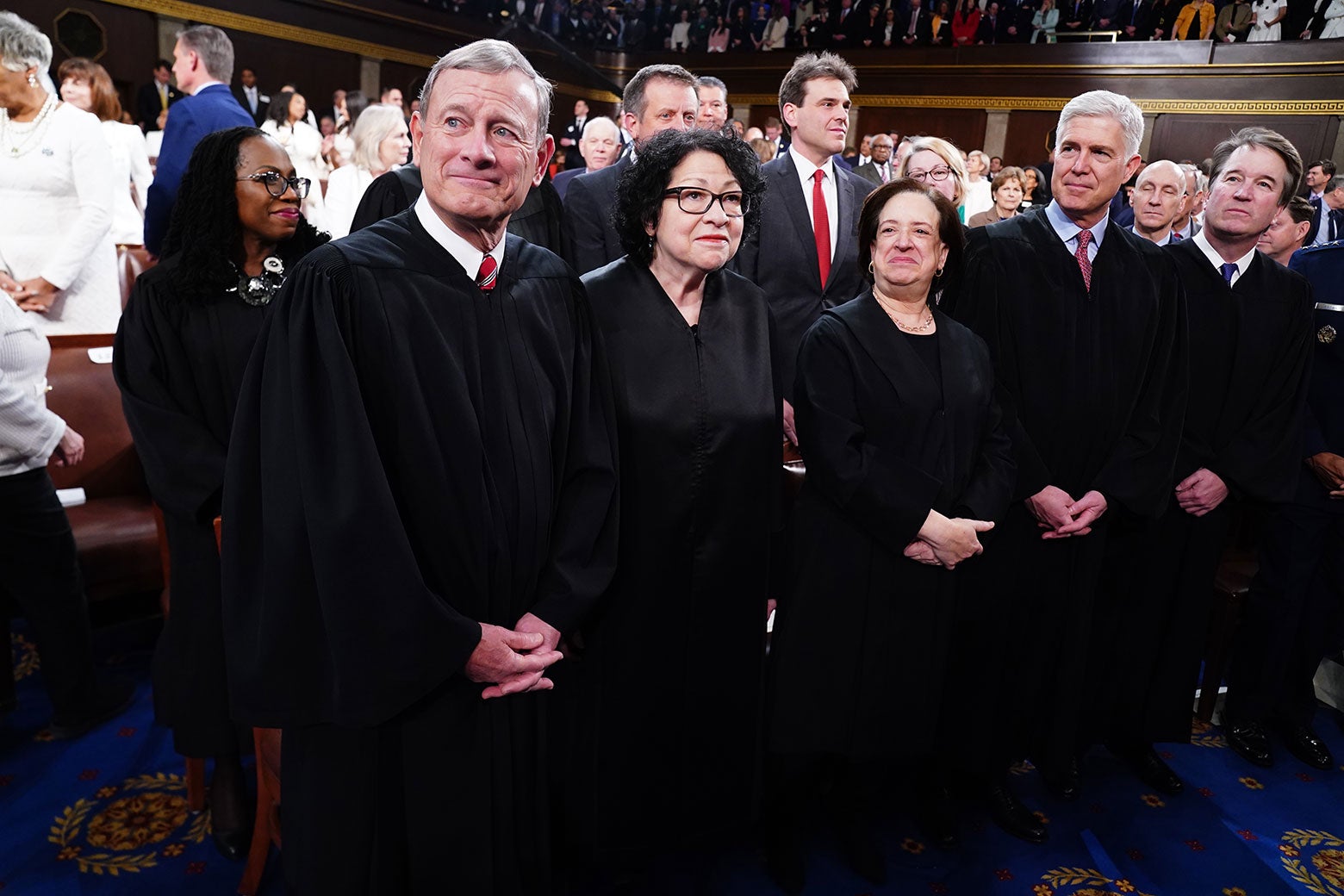

Shawn Thew/Pool/Getty Images

Among the election cases blowing up this Supreme Court term, several cases dealing with online speech could have a major impact on the tidal wave of disinformation that already threatens to wash away sense and truth in 2024. New technologies are supercharging online disinformation, which as we know, quickly turns into real-life conflict. At the same time, laws and regulations around speech and online content are stuck in the past century. On this week’s Amicus podcast, Dahlia Lithwick was joined by Barbara McQuade, former federal prosecutor and author of Attack From Within: How Disinformation Is Sabotaging America, to discuss whether and how the courts might handle a dizzying array of new threats to election integrity from social media and disinformation. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Dahlia Lithwick: The United States is uniquely susceptible [to disinformation] in part because of the First Amendment, in part because of a legal regime under which we operate, and this notion that for better or for worse, the marketplace of ideas is the way to go. You talk about how corrupt and corruptible the marketplace of ideas is. But I find myself struck by the twin facts that we have archaic doctrine that cannot possibly metabolize technological change fast enough, and then we also have these archaic ideas about how a marketplace of ideas could work. Do you mind just thinking through the ways in which it’s almost overdetermined that we can’t get control of this because of the constraints of the First Amendment?

Barbara McQuade: I think we can, but I do think that it makes it really challenging. We all cherish the First Amendment; people on the left, on the right, and in between. Everybody understands why the First Amendment is so important. And so it makes it difficult to say “We’re going to ban disinformation,” because who is the arbiter of what is disinformation and what is not? But we need to rethink social media and whether it’s completely hands-off. As you well know, no right is absolute, including our First Amendment rights to free speech. As long as there is satisfaction of strict scrutiny—that is, a compelling governmental interest and a limitation that is narrowly tailored to achieve—that interest does pass constitutional muster.

So I think we need to think about that online. People refer to social media as the virtual town square. Elon Musk loves to say that this is the modern town square. But it’s really different from the town square, right? It’s very different from a real person standing on a soap box in the town square. In the town square, we can see who’s speaking. Is it really a Black activist or is it a Russian guy in a hoodie? We can assess their credibility based on who it is. We can also see how other members of the public are responding. Are people cheering? Are they booing? Are they just walking by and ignoring this person?

Whereas online, people get likes and shares that may be generated by bots. It might be controlled by the speaker themselves, but we don’t know that. So they can create the illusion of popularity when it may be that no real people are liking and sharing that message at all. So the parallels don’t work the way they do in real life. But I do think that we can regulate social media even without addressing content, and that might be the way to do it. Content-based regulation is where you get into trouble with the First Amendment.

But there are other things we could do—like regulating the algorithms, the computer code that tells programs what to do. A couple of years ago, there was this Facebook whistleblower named Frances Haugen. She was a data scientist at Facebook and she disclosed that Facebook was designing algorithms to deliberately generate outrage. Because if you were outraged, you were more likely to stay online. More eyeballs would be on the ads, and the platform would make more money. So people were being manipulated so that Facebook could turn a profit. You know the old phrase, “If you don’t know what the product is, it’s probably you”? Turns out it was true at Facebook. So we could have regulations that say that algorithms may not be used to manipulate people to generate outrage, or at least require disclosure of those algorithms, so that people would know which platforms are trying to use them to generate outrage.

The other thing that these social media companies do is they microtarget people to the most minute degree such that they know what messages are going to resonate with you. So I’ve been shopping for winter boots and suddenly I see ads for winter boots everywhere. Wow. How did they know? Well, they know because of my search history and because of the things I’m clicking on and what I’m communicating with, but they know, down to every detail, everything there is to know about us. And so we get bombarded with certain messages that only we see and maybe other people aren’t seeing. And when you and I are not seeing messages other people are seeing, it’s very difficult for us to rebut them. Only people in certain echo chambers are hearing certain messages about “2000 mules,” or whatever the allegation of the day is, and it’s difficult for the rest of society to rebut that the way we could if it were out there in the public domain.

And so perhaps disclosing some of the ways groups are being microtargeted, which microgroup we are in, how we’re being sorted, we could require disclosure of all of those things.

I want to ask you, because you’re so steeped in these questions of data privacy and national security and technology, what you made of oral arguments in these content moderation cases. I’m trying to be generous when I say that you have a Supreme Court who’s just in this complete mashup of technology they don’t fully understand. They’re searching for a metaphor: Is it a publisher or is it a phone company? [What should they do with] Section 230? There’s so many pieces of this, and all due respect to the court, they never cover themselves in glory when they do these technology cases.

I think it was Justice Kagan herself who said last term, talking about some of these cases, that the last people you want deciding these issues is nine people in black robes, because we don’t get it, we don’t understand any of this. It is a challenge as technology becomes more complicated. I know I’ve talked to a judge who served on the FISA court, where the technology that they’re dealing with now for surveillance techniques has become so complicated that they need technical amici to help explain how the systems work.

You’re talking about the two Netchoice cases, Netchoice v. Paxton and Moody v. Netchoice, that are challenging these laws passed in Texas and Florida that would say it is illegal for social media platforms to remove content that violates their community standards. It’s really interesting because each side is sort of accusing the other of violating their free speech rights. The states say that the social media platforms are engaging in censorship when they take content down, and the social media platforms are saying, “You are violating our First Amendment rights by forcing us to say things that violate our terms of service. We don’t want bullying and harassment and threats on our platforms because our business model is all about having a safe space for conversation. And you know, sometimes people are a little bit provocative, but we wanna take down anything that might be hurtful or dangerous.” And so it’s this First Amendment faceoff. “No, you’re violating my First Amendment rights.” “No, you’re violating my First Amendment rights!”

There were two justices—no surprise, I suppose—Thomas and Alito, who actually did say: How is what you’re doing anything but censorship? So, they seem to have their minds made up [as to] who was violating the First Amendment.

But it seems to me social media platforms are private actors. I don’t see how they can possibly violate anyone’s First Amendment rights and engage in censorship that would violate the First Amendment, because they’re not state actors. They’re private entities, so I think they get to decide what goes on their platforms and what doesn’t. So I think they’re going to win these cases.

It does raise a bigger issue, though, of how to think about social media platforms. On the one hand, they want to say, “We’re publishers and we should enjoy the same editorial discretion that the New York Times enjoys.” On the other hand, they say, “But we’re not publishers when it comes to defamation laws, because there we get this immunity under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. We’re just a platform! We’re like the soap box in the town square, we’re not involved in content in any way, we just provide this place where people can come and talk.” So it kind of seems they want to have it both ways.

At some point we have to adjust the way we think about social media platforms. They don’t really fit squarely into any category, so I think we need to think carefully. We’re probably overdue for some adjustments to Section 230. I don’t know exactly what that might look like, but it does feel like a little bit of a square peg in a round hole the way we’re trying to deal with it right now.

And then we’ve got this other case coming down the pike in the Murthy case—about whether the Biden administration violated the First Amendment when it asked social media companies to consider removing certain content that was dangerous to public safety, about COVID remedies and other kinds of things.

I suspect that their ability to jawbone with social media companies should remain permissible. But that is a concern too. How heavy-handed can they be in telling social media companies what they can and cannot post? I think as long as it’s a request and not a demand, it should be OK. But we’re really struggling with figuring out how we deal with this huge part of our lives that doesn’t really fit any of our traditional ideas of how speech works.

Discover more from CaveNews Times

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

![Exploring the Serene Beauty of Nature: A Reflection on [YouTube video title]](https://cavemangardens.art/storage/2024/04/114803-exploring-the-serene-beauty-of-nature-a-reflection-on-youtube-video-title-360x180.jpg)